We all started out programming somewhere. Whether you are a self-taught developer starting out, a computer science major or a 20 year veteran, you all know that even the bad/unreadable code works. In my earlier blog post "Why Coding Conventions Matter", I talk about writing maintainable and readable code.

There are a number of resources out there about this subject, and I would highly recommend Robert C. Martin's (Uncle Bob) book Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship. And also his website Clean Coders.

Code Smell

Code Smell is a technical word used to describe the quality of code. Determining what is and is not a code smell is subjective, and varies by language, developer, and development methodology. It is often a word used to describe code that you don't like. In that sense, it is synonymous to ugly, dirty, unclean, repeated...etc.

There are a few reasons why our code smells:

- Duplicated Code

- Methods too big

- Classes with too many instance variables

- Classes with too much code

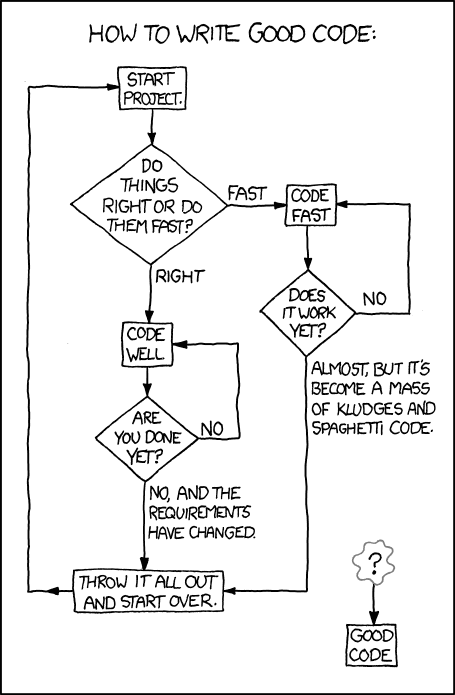

There is a consensus that clean code can help drive productivity in a software development company. When we are trying to build a prototype, a proof of concept or a minimum viable product, the code may start out as a big jumble mess to get something working but in all cases we should always refactor the code to be maintainable and readable in the end. So what are the characteristics of clean code?

Let's take a look:

- It should be elegant — Clean code should be pleasing to read. Reading it should make you smile.

- Clean code is focused — Classes and functions are Single responsibility principle

- Minimize the number of entities such as classes, methods, functions..etc.

- Clean code is taken care of. Someone has taken the time to keep it simple and orderly. They have paid appropriate attention to details. They have cared.

- Contains no duplication of code – DRY principle

How to write clean code?

Naming Conventions

The name of a variable, function, or class, should answer all the big questions. It should tell you why it exists, what it does, and how it is used. If a name requires a comment, then the name does not reveal its intent. Therefore, name elements on the basis of what they are and make it a habit to maintain a convention throughout your code. Ensure that names are pronounceable.

// Bad

DateTime d = DateTime.Now; // current datetime

// Good

DateTime now = DateTime.Now;Boolean Names — variables or methods that return a boolean value, should start with "is", "has", "can" or "should"....or something similar to define the yes/no action.

// Bad

var admin = identity.IsInRole("Admin");

// Good

var isAdmin = identity.IsInRole("Admin");Class Names — Classes and objects should have noun or noun phrase names like Customer, WikiPage, Account, and AddressParser. This also matters on what the intent of the class is. In the .Net Mvc world, you would never name your Controllers without containing the word Controller in it like HomeManager instead of HomeController. Same goes for ViewModels, ContactData instead of ContactViewModel.

Interface Names – Interfaces usually use letter "I" as prefix with name of interface. After letter I, use Pascal case.

namespace CleanCode

{

interface IEmployee

{

void GetDetails();

}

}Method Names — Methods should have verb or verb phrase names like PostPayment, DeletePage, or Save. Accessors, mutators, and predicates should be named for their value and prefixed with get, set. Also, methods should be named for what they do, not how they do it. You may change the implementation later and you shouldn’t need to refactor your consuming code because of it.

// Bad

public IEnumerable<Post> GetFromSql()

{

}

// Good

public IEnumerable<Post> GetPosts()

{

}Pick One Word per Action — Pick one word for one abstract concept and stick with it. For instance, it’s confusing to have fetch, retrieve, and get as equivalent methods of different classes. How do you remember which method name goes with which class?

File Names – Your file names in source code should ideally match your class or entrypoint names. Naming things differently will cause confusion by other contributors of the code. You should always try to strive to keep them in sync.

// Bad - BlogPost.cs is named different that class name

public class Post

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public int Description { get; set; }

}

// Good - use Post.csMethods

The first rule of methods is that they should be small. This implies that the blocks within if statements, else statements, while statements, and so on should be a few lines long. Anything more than a few lines of code results in a high degree of cyclomatic complexity. Cyclomatic complexity is a software metric, used to indicate the complexity of a program. The more independent paths the code has, the harder it is to read and therefore debug and maintain.

Method Arguments

A method shouldn’t have more than 3 to 5 arguments. This definitely isn't a hard number but keep it as low as possible. When a method seems to need more than three arguments, you probably should wrap the them into a class.

Below, you can see how the code is cleaner by making a class out of arguments. Not only does it look cleaner, you can now easily refactor the class object without breaking the signature of the method.

// Bad

public void Update(int id, string name, string description, string[] tags, string isPublished)

{

}

// Good

public void Update(Post post)

{

}Comments

Comments in code may be perceived as problematic. There are instances on when and how to go about commenting your code. Some languages, like c#, allow you to document you code to be exposed for IDEs. There are also tools like DocFX, to allow you to generate documentation from source code. This is considered good practice especially when you are writing code that is going to be consumed by other developers.

Add comments only to explain convoluted thoughts. Fewer comments reduces clutter.

// Bad

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> Create([FromBody] CreatePostViewModel model)

{

// Check if Model is valid

if (!ModelState.IsValid)

return BadRequest(ModelState); // return bad request if not

try

{

// post result from command

var resultFromCommand = await _mediator.Send(new CreatePostCommand(model));

// return ok if successful

return Ok($"Post with Id '{resultFromCommand.Id}' has been created.");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

// Add model error and return bad request

ModelState.AddModelError("", ex.Message);

return BadRequest(ModelState);

}

}In the clean version, we rename the result variable to better describe what is returned, thus eliminating the need for comments since the code is self-explanatory.

// Good

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> Create([FromBody] CreatePostViewModel model)

{

if (!ModelState.IsValid)

return BadRequest(ModelState);

try

{

var post = await _mediator.Send(new CreatePostCommand(model));

return Ok($"Post with Id '{post.Id}' has been created.");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

ModelState.AddModelError("Error creating post", ex.Message);

return BadRequest(ModelState);

}

}Clean code doesn't (necessarily) take longer to write

Clean code always looks like it was written by someone who cares. – Michael Feathers

Initially your code may be messy as your starting out with your thoughts and trying to get things to work. You can refactor the code, after it's working, into smaller chunks and fewer lines, each with a single responsibility. Remember, you are writing code not only for yourself but for others that may be supporting your code.

Recommended Resources

- Clean code: A handbook on Agile Software Craftsmanship – Please note that the source code in this book is all in Java. However, you can still benefit from reading this book. This is divided into three parts. The first describes the principles, patterns, and practices of writing clean code. The second part consists of several case studies of increasing complexity. Each case study is an exercise in cleaning up code—of transforming a code base that has some problems into one that is sound and efficient. The third part is the payoff: a single chapter containing a list of heuristics and "smells" gathered while creating the case studies. The result is a knowledge base that describes the way we think when we write, read, and clean code.

- The Clean Coder – Another book by Uncle Bob. Martin introduces the disciplines, techniques, tools, and practices of true software craftsmanship. This book is packed with practical advice–about everything from estimating and coding to refactoring and testing. It covers much more than technique: It is about attitude. Martin shows how to approach software development with honor, self-respect, and pride; work well and work clean; communicate and estimate faithfully; face difficult decisions with clarity and honesty; and understand that deep knowledge comes with a responsibility to act.

- Code Complete – No matter what your experience level, development environment, or project size, this book will inform and stimulate your thinking — and help you build the highest quality code.